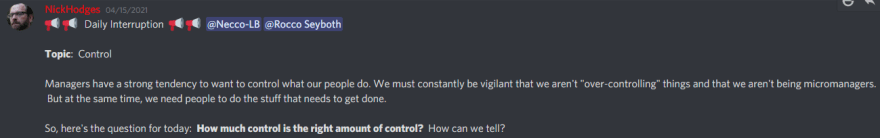

Every morning, I see the unfiltered thoughts of 1400+ engineering leaders as one of the community moderators in the Dev Interrupted Discord server . We start every day with a Daily Interruption topic about how to make agile work in real life; scaling teams, building culture, hiring, continuous improvement, metrics — fun stuff like that.

Recently this Daily Interruption popped up and stopped me in my tracks:

How much control is the right amount of control?

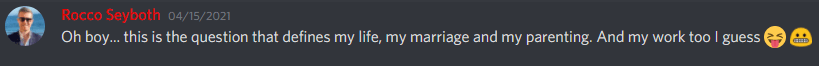

Nick might as well have asked, “what is the meaning of life?” You can see my immediate reaction was bewildered introspection. 👇

A bit of context…

I was born with a default control setting of 10 (out of 10). I believe your strength is your weakness. At least in my case, this has proven to be true. Like many controlling people, I take ownership, obsess over little details and get the job done. Also, like many controlling people, sometimes I have a hard time working with others. I’m putting it mildly. 😄

So what do you think happened when I got my first job working at a software start-up?

As an individual contributor, I crushed. My super controlling nature propelled me to dominate every task that was assigned to me. I overachieved.

Then I got promoted. And just like my friend Dan Lines said about being promoted from dev to team lead , “a freight train hit me.”

Since then I’ve been on a journey to figure out how much control is the right amount of control when it comes to leading software teams. I’ve been managing people for sixteen years now and I can break that time into three distinct phases:

My three phases of controllingness

Phase 1

When I first got promoted to team lead I was highly controlling. I literally did most of my team’s work for them. I worked seventeen hours a day six days a week to ensure every single task was completed to my exact specification. The people that worked for me were unhappy (some actively disliked me personally) but we got results that the CEO cared about so it went unnoticed.

And I was good at managing up, so I actually got promoted for this behavior! I was in my early twenties and motivated by the wrong things (power, money, and, of course, control). I look back on the period with embarrassment and I’ve actually apologized to many of the people who worked for me back then.

Phase 2

I’m a person of extremes so when I realized micro-management was wrong, I naturally swung the pendulum in the exact opposite direction. I told myself I was hiring smart people and I should leave them alone. I’m good at hiring so it kind of worked. But, again, the people who worked for me suffered — this time in a way that they noticed much less. Good people actually want feedback! It’s not good for their work to go unchallenged because then it’s harder to improve. My teams in Phase 2 all had a lot of fun and liked each other but we were a bit chaotic in how we got work done and we were not living up to our potential.

Phase 3

I like to think I’m currently in Phase 3 which is more of a happy medium. I try to do four things to attempt to strike the right balance:

Write super clear job descriptions and goals so every person knows which areas they own and which outcomes they are responsible for driving for the business.

Provide extremely honest feedback… sparingly. You have to pick your battles. I find a lot of feedback is good upfront for new employees. And then, over time, you have to give people room to make their own choices or make mistakes. I find my people actually prove me wrong a lot of times when I think they are going to make mistakes anyway which is a good reminder to keep my mouth shut.

Occasionally I decide I’m going to personally own something that needs to be handled my exact way — like when an important new project needs to be bootstrapped with care and skill. In those cases, I let my control freak flag fly and I just do it my way. It’s ok to do this very rarely.

I warn everyone upfront I am a recovering controlling jerk and apologize constantly for when I step over the line which I still do all of the time. 😁

Phase 2 is just as bad as Phase 1

Managers in phase 1 get all of the credit for being the worst but we should not underestimate the damage that can be caused by phase 2 controlling managers — ones who do not “control” enough.

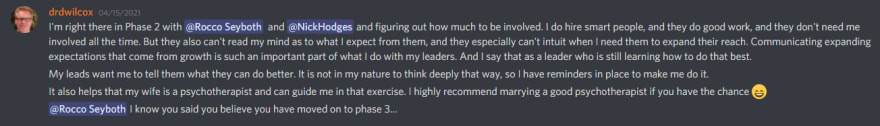

I found this response from drdwilcox (a VP of Engineering) fascinating.

When I reflect back on my time in Phase 2, I realized it was my own insecurity that stopped me from communicating and coaching more. Once I put my imposter syndrome aside and realized I just needed to do my best for everyone on my team, I was able to strike a balance between too much input and too little feedback.

Engineering metrics — a tool for good and evil

“Communicating expanding expectations that come from growth is such an important part of what I do with my leaders.”

Engineering metrics are probably the most common topic in the Dev Interrupted Discord as well as on our podcast (with the same name) . Everyone has ideas about which metrics are good and bad and everyone has a story about a time that a bad manager used metrics to control their team in a negative way.

Phase 1 managers often use bad metrics to stack rank engineers and pit them against one another or just force them to work harder. Phase 2 managers don’t share enough data and miss an opportunity to use good metrics to unite the team.

If you’re trying to become a Phase 3 manager, our community has tons of resources about how to use metrics to help your people improve and increase quality and efficiency among your teams.