“Yesterday I worked on feature X. Today I’m working on feature Y. No blockers.”

Sound familiar? It’s the update your new junior developer gave in the stand-up meeting this morning. You told them not to ramble, but this isn’t really what you had in mind. When you were explaining stand-up 101, you told them to:

Show up on time. This is the most important thing you can do. If you’re five minutes late for a fifteen-minute meeting, it screws everyone up.

Pay attention. The whole point of the meeting is to 1) get a cohesive view of what’s happening across our entire team which will help us do our own work better and to 2) hear where our teammates are blocked so we can help them. We can’t do either if we’re checking email or reading about how to configure SSH over AWS SSM or thinking about the Tangle Tower puzzle (Poppy’s metronome!!) that was jamming us up last night.

“Hello! I’m Miki. I’m a junior dev at LinearB but I always pay attention in our stand-up. (unless, of course, Dan asks me to take a selfie for his blog 🙂 )”

“Hello! I’m Miki. I’m a junior dev at LinearB but I always pay attention in our stand-up. (unless, of course, Dan asks me to take a selfie for his blog 🙂 )”

Come prepared. There’s only three things we need to know so this one should be easy, right? Actually, coming prepared means a lot more than just knowing what I did, what I’m doing and if I’m blocked.

Most new devs get the basics down right away. But when do we start holding them accountable for a higher level of contribution?

In addition to writing good code, there’s a bunch of other important responsibilities that fall under the category of “being a good teammate”.

I break down “being a good teammate” into four categories.

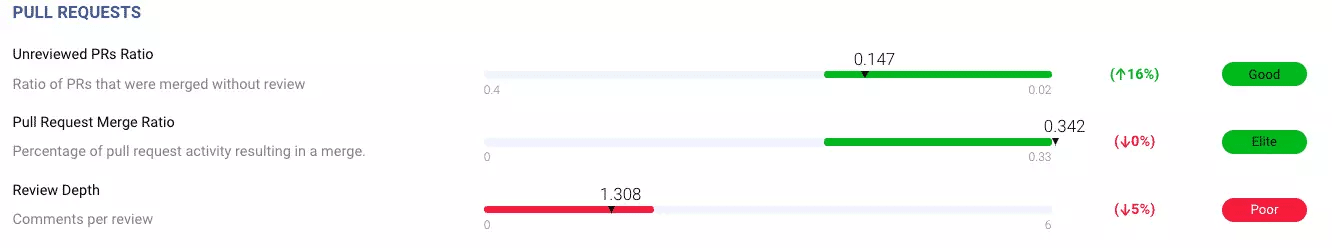

Pull Requests (PRs):

- Participate in the review process.

- Pick up PRs in a timely fashion.

- Provide actionable feedback.

Reviews can be intimidating for new devs which sometimes causes them to stay on the sidelines.

Before your next stand-up, tell your junior dev. . .

to find a pull request that has been sitting out there for a few days and share in the meeting that they are going to work on it today. If they actually do it, not only will they impress their peers but they’ll learn a lot too.

I like to coach our senior devs to accept the feedback openly and encourage it. That rewards the behavior and creates a positive cycle.

Reliability:

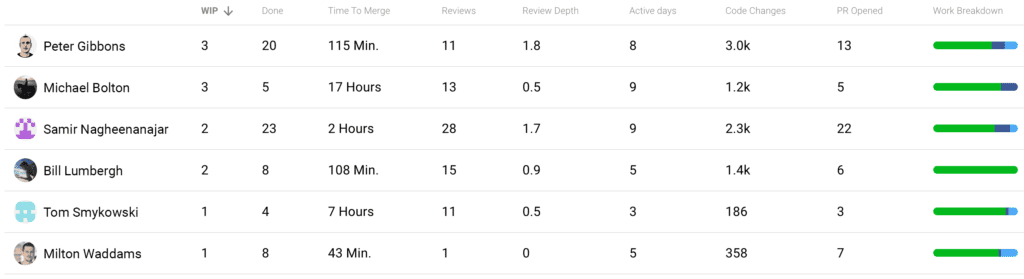

New devs are notorious for taking on too much during your iteration planning. Which is great, but they are also notoriously bad at knowing when they are behind schedule in the iteration (not so great). How many times have you listened to a new dev say they’re “all good” in the stand-up but there’s only three days to go in your iteration and they have 4 WIP (active branches) open. You know they aren’t going to finish. They don’t have a clue.

Before your next stand-up, tell your junior dev . .

to check the number of WIPs everyone else on the team has open. Why? This will give them a frame of reference about how they’re doing compared to their peers. If everyone else has 1-2 and they have 4 open, this signals they may have a problem and give them an opportunity to ask for help in the meeting.

Everyone is counting on them to do what they say they’re going to do. Eventually, they’ll be much better at predicting if they are going to finish on time. In the meantime, you can help by giving them benchmarks to compare themselves to.

I like to announce how many days are left in your iteration at the beginning of your stand-up. It helps the whole team and frames the conversation that is about to happen.

Quality:

Experienced devs know when they’re in risky territory and ask for help. In fact, experienced devs plan ahead well which keeps them from getting into trouble to begin with. On our team we talk a lot about four types of risky work:

- Risky merge which we define as pull requests being merged with no review – either because nobody picked up our PR or because we merged too quickly for anyone to pick it up (“It’s such a small change, nothing bad can happen…”). Our team also lovingly refers to this scenario as lightning PRs.

- Risky review is one where a review did happen but there were either very few comments or the comments lacked depth.

- Risky branch which we define as diff size large (diff from the main trunk) + refactor ratio large (basically it means touching a lot of existing code)

- Another type of Risky branch is with PRs that have been sitting out for 30 days or longer. We sometimes call these long living PRs. They’re risky because the more time that passes the more the earth (our code base) moves under our feet.

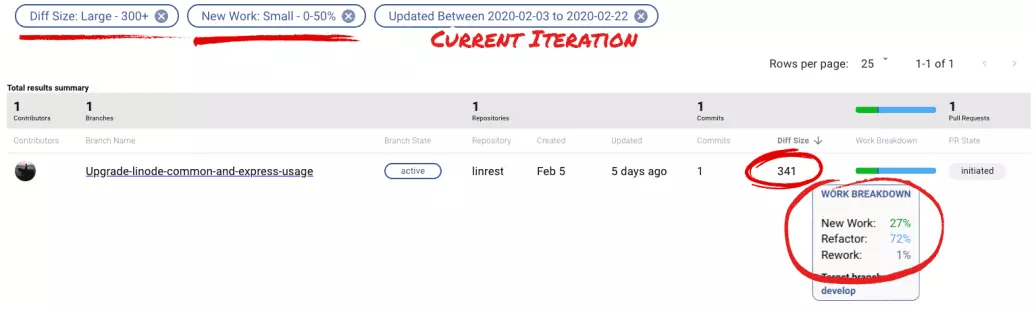

Find risky work in your current iteration

Find risky work in your current iteration

We’ve found that the presence of any of these high risk scenarios leads to a high likelihood of production bugs later on. And, even if the issues don’t reach customers, they can extend your overall cycle time, cause you to miss your iteration deliverables, and maybe even cause you to push your release because of extended review cycles or difficulties during merge. So we look at these situations closely. But if you’re relying on your devs to self-report, you risk your junior devs not knowing they have risky work.

Before your next stand-up, tell your junior dev

to check the presence of risky work and to bring it up in the meeting if they have any. It will help the rest of your team prioritize those PRs accordingly to make sure you catch any issues early in the process. As the team leader you may ask a senior dev to do an early review on the branch to see if the high code change rate is really needed. Or maybe the design is off. In extreme cases you might even reassign the work (though I personally almost never do this because you lose a big teaching moment).

Our team believes in the “shift left” mentality and for us it goes way beyond automation. We pride ourselves on calling out potential issues early in the process. It’s a mindset that helps us strive toward operational excellence.

Scalability:

Even when you have a junior dev who writes effective code, sometimes they forget they aren’t working in a silo. I’m constantly asking our devs about two types of scalability

Product scalability:

- Do you have a plan for load testing?

- Have you allocated time for performance testing?

- Do you have a progressive roll-out plan that you’ve communicated to your PM?

- Is your documentation thorough?

- Have you reviewed your API with your internal customers?

- Will your teammates understand what you did without you there to explain?

One signal that your code is not scalable is the amount of time spent on your PRs compared to the rest of the team.

Before your next stand-up, tell your junior dev . . .

to look at their average time to review and compare it to others members of the team. If it’s substantially higher, that is a good leading indicator they aren’t doing enough work up front.

And during the stand-up tell your junior dev to think about each person’s work as they talk and figure out if anything they’re doing will affect them – positively or negatively. We don’t want them to derail the meeting of course. They can pull them aside after. They’ll quickly learn that a hallway conversation now may save them a lot of trouble when they merge.

If your team already tracks and publishes metrics for WIPs, PRs, re-work, etc, it doesn’t take a lot of time to check before the meeting. Going the extra mile to show up prepared for the stand-up will help your junior devs gain credibility with their team, contribute more to your overall iteration, and do better work themselves. And of course it will help them progress in their career so they can take on more responsibility and more interesting projects.

We give all of our devs (junior and senior) a personal dashboard with these metrics. Not only has it made our stand-ups more efficient, but it helps everyone on the team see where they can improve from sprint to sprint.

For the other team leads out there, how do you help your junior devs be better teammates? If you have a novel idea for onboarding junior devs or running a great standup, hit me up at dan@linearb.io. If it’s great, maybe we’ll feature it on an upcoming blog!