Pull requests are at the core of using GitHub, regardless of whether we’re talking about open-source or private projects. The pull request process not only serves as a gate for code but also creates opportunities for discussion and exchange of knowledge. It also acts as documentation for code decisions.

In this post, we’ll cover a very specific—yet very valuable—aspect of the pull request process: the different ways in which you can approve a pull request on GitHub.

We’ll first explore some fundamentals, defining GitHub pull requests and offering a brief explanation about how they work. Then we’ll dive into different ways that you can approve GitHub pull requests.

By the end of the post, you should know more about some of the options at your disposal and why some of those options represent anti-patterns you should be aware of.

What Is a GitHub Pull Request?

Let’s start with the “what” and “how” of GitHub pull requests (PRs).

A pull request (called a “merge request” in GitLab) enables a contributor to request approval of their code changes before it is merged.

The pull request process is a core tenet of how many teams work. It can serve as a protective barrier, guarding the quality of the code and helping to avoid merge conflicts, bugs, and the dreaded outage. Additionally, PRs create a nice opportunity for reviewing the code, discussions, and exchange of knowledge.

If you use continuous integration and continuous deployment—and you should—PRs represent a nice spot for the implementation of quality gates. Before a branch is merged into the mainline, you have the perfect opportunity for running automated tests and doing all kinds of useful checks.

Finally, pull requests are a great piece of documentation. The discussions that take place while reviewing proposed changes become invaluable historical records for people in the future who will seek the context and motivation behind certain changes.

How Does a Pull Request Work?

For open-source projects, the pull request process typically works like this:

- Find an open-source project you want to contribute to and fork it (i.e. create a copy of it using GitHub’s UI)

- Clone the Git repository locally

- Start working on your task or fix on a new branch—usually created off of main, though different projects might use different workflows

- Push the changes to your own fork of the repository on GitHub–commonly known as a commit

- Go to the original repository’s page and use the UI to create a pull request

- Submit it to a peer for review and approval–once the pull request is opened, it cannot be approved by its creator.

So, for open-source contributions, there will be at least three repositories you must be aware of: the original repo, your GitHub fork, and your local repository. This is called the “fork and pull model.”

For private repositories, things are generally a bit more simplified. Instead of having to create your own fork, you’d typically have Git push access to the same repository. You’d then clone this repository.

From this point on, the process would be the same. This is called the “shared repository model,” and it’s what small open-source teams and private companies use.

How to Approve a Pull Request in GitHub

As it turns out, the GitHub pull request process is quite flexible, accommodating many different styles and workflows. I’ll now walk you through several different ways in which you can approve a PR on GitHub.

(1) Approving Without Review

Let’s start with the worst possible scenario: when people approve PRs without any kind of review. Except when it comes to the most trivial of changes (e.g., fixing typos or improving the formatting of some class), approving PRs without reviewing them is a terrible anti-pattern.

While PRs should all be reviewed before approval/merging, it doesn’t necessarily need human intervention. gitStream–a free workflow automation tool–can review and approve safe changes (like docs updates) and free up resources to focus on more important and sensitive PR reviews–like security updates or sensitive files.

PRs merged without reviews are signs of serious problems inside a team or organization. PR size might be one of them.

Large pull requests are hard for the reviewers, so many might simply give up and just accept them by default. Lack of team conventions and strong governance models also come to mind—after all, it shouldn’t even be possible to merge PRs without review. Large PRs also negatively impact cycle time as they take longer to review–so they sit idle longer.

LinearB provides real-time alerts to notify you and your team when large PRs are created. Teams can also use this alerting to remind the team of any goals set around this metric–helping the team adopt good habits and keep PRs small.

In addition to alerts, teams can use gitStream to automatically apply labels to PRs that provide additional context (like estimated review time) to help reviewers prepare, prioritize their day, and minimize the cognitive load.

Improve your code review process with alerts for PRs merged without review. Get started with our free-forever account today!

If a PR is approved without review, there are ways to deal with that, which include reverting the PR or even performing a review after the fact.

(2) Closing Without Approving

It’s also possible for a reviewer to close a PR without approving it. This might sound harsh, but it’s actually better for the health of the codebase than blindly approving all PRs.

In the context of open-source projects, maintainers will often close PRs that don’t follow the contributing guidelines of the project. They might even use bots to automatically check some requirements and close the PRs that don’t adhere to them.

In the context of private projects, outright closing PRs is rare. Typically, at least some discussion will take place before the submissions are either accepted or rejected.

(3) Having Required Reviewers

Using GitHub’s branch protection settings, you can configure several different options for your repos. Among them, you can determine that a given number of approvals is needed for PRs to be approved. You could also use gitStream to mandate that certain PRs have to be reviewed by certain teams.

For instance, you might want to enforce a rule that the branch needs at least two approving reviews to merge a pull request.

(4) Accepting After Offering Feedback

On GitHub, there are some different forms of feedback you can provide:

- General comments: These are PR-level comments, grouped in the “conversation” tab of the PR page

- File comments: You can add individual comments to any changed lines of any altered file

- Review: This is an “official” review, which can contain one or more comments.

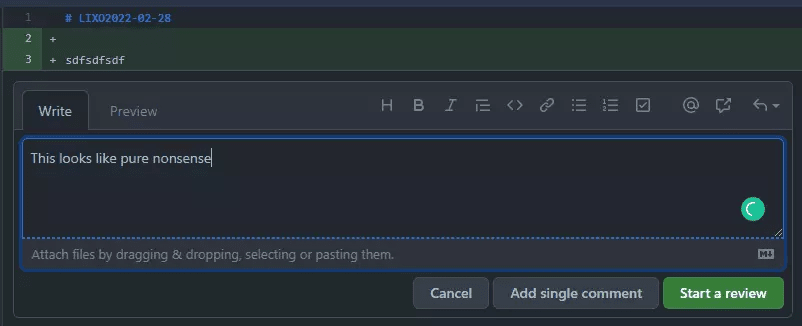

As the following image shows, when giving feedback on lines, you can choose to add a single comment or start a review:

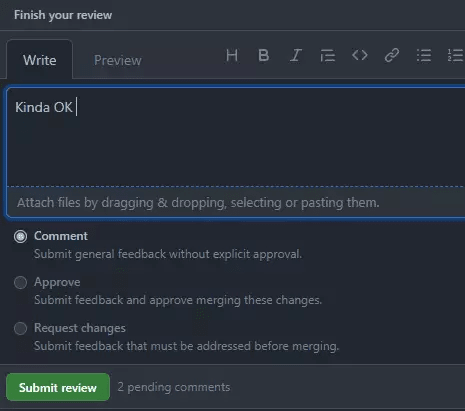

When you decide to submit a review, you must provide a comment with one of the following three statuses:

- Comment: This is a comment that doesn’t explicitly approve or reject the changes

- Approve: This feedback closes and accepts the PR

- Request changes: A great use case is if a deprecated component is used--This type of feedback keeps the PR open while it’s not addressed

To act upon a piece of feedback, the person submitting the code will typically:

- Go back to their local repository

- Perform the necessary changes

- Commit and push those changes

GitHub automatically picks up the changes and updates the PR page.

This style of approving merges typically leads to higher-quality code. Setting thresholds for the number of comments per PR would have similar code quality benefits to setting a rule that a branch needs two approvals to merge a PR.

With LinearB, you can set customized thresholds, and WorkerB will warn your team when a PR with a basic review is about to be merged. Then you can measure your team’s review depth over time.

We’ve found that as review depth increases, code quality increases, cycle time improves and unplanned interruptions caused by code churn are reduced. All of this allows your devs to spend more time on new features (value creation).

Avoid superficial LGTM reviews. Use Team Goals + WorkerB to reinforce good habits around review depth. Get started today!

(5) Testing the Branch Locally

This is probably the most labor-intensive style of approving PRs. Sometimes the change is so complex or critical that the reviewer feels the need to pull the branch to merge it and test it locally. There might be the need to solve merge or logical conflicts, fix broken tests, or perform other types of corrections.

However, best practices are that testing and code review ought to be two distinct activities. If the reviewer feels the need to do this intensive form of review, it’s a troubling sign.

Why Are Certain Approval Processes Better?

The pull request process is at the core of the software development lifecycle. However, it can derail into anti-patterns if you don’t give it the care it deserves.

This post covered some of the styles of review you can adopt when approving pull requests. As you’ve seen, most of them represent some kind of anti-pattern.

Our research shows that the perfect PR is the one that’s small, focused, generates some amount of healthy discussion, and doesn’t take too long to be reviewed and merged. If you’ve discovered that your cycle time is too high and the culprit is your pull requests process, or specifically your PR review time, be wary of how you encourage your team to improve these metrics. It’s not merging without review, and it’s not superficial, less thoughtful review comments.

It is by gaining visibility into and addressing leading and lagging indicators metrics and then working to improve them with programmable workflows.